2 Million Blossoms: New Beekeeping Magazine to Debut

In January, a new quarterly beekeeping magazine featuring the photography and scholarship of local favorite Dr. Kirsten S. Traynor will debut! Titled 2 Million Blossoms, the quarterly magazine will offer short and long form articles exploring how bees, birds, butterflies and bats enhance our planet. Dr. Traynor is the former editor of American Bee Journal and IBRA’s Bee World.

Dr. Traynor is the former editor of American Bee Journal and IBRA’s Bee World.

While the magazine will include beekeeping, its content will cover the full range of pollinators and sustainability issues..

It's mission is "To awaken readers to the vast diversity of pollinating insects and animals. To delight, entertain and name those well-adapted creatures buzzing through our world, because the more we know about pollinators, the better we can provide habitat."

Authors in January include Dr. Marla Spivak, Dr. Dave Goulson, Dr. Mark Winston, and more. An annual print subscription is $35, a digital subscription is $20.

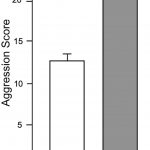

Honey Bees and Power Lines, Revisited

Exposure to electromagnetic fields caused aggression to jump

Exposure to electromagnetic fields caused aggression to jump

A team led by Sebastian Shepard of the University of Southampton and Purdue has found that honey bee colonies subjected to extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields like those emitted from a variety of sources that include power lines, increased aggression scores by 60% in response to intruder bees from foreign hives. These results indicate that short-term exposure to these fields at levels that could be encountered in bee hives placed under power lines, reduced aversive learning and increased aggression levels.

Flowers as viral hot spots

The University of Vermont's Samatha Alger has uncovered a potential route by which the RNA viruses of honey bees (like Deformed Wing Virus) can be transmitted to non-managed species. The team first examined if honey bees deposit viruses on flowers and whether bumble bees become infected after visiting contaminated flowers. The experiment determined that honey bees do deposit viruses on flowers, but unevenly, suggested more factors are at play. Happily, the team did not detect infection of a bumblebee by such viruses over the course of the experiment, though DWV has been widely transmitted into British bumblebees.

Overview of the Fight Against Varroa

Credit: USDA-ARS, Electron and Confocal Microscopy Unit, Beltsville

Scientific American recently posted a helpful overview of the state of the fight against the varroa mite, including discussions of the history, state of the science, current weapons (and their vulnerabilities) and emerging threats. Among key points: Amitraz may be losing effectiveness, and commercial beekeepers are reluctant to adopt resistant stock. It's a great review that might belong in our upcoming beginners' courses!

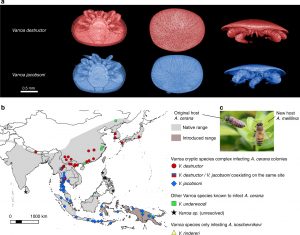

Two Varroa Genomes Sequenced

Researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University sequenced the genomes of the two Varroa mite species (V. destructor and V. jacobsoni) that parasitize honey bees, finding that each species used a distinct strategy to survive in its bee host, potentially overwhelming the bees' defenses. In addition to pointing to how scientists might vanquish these deadly intruders, the findings also shed light on how parasites and hosts evolve in response to one another. The species share 99.7% of their DNA, but genetic evidence indicated that the mite species followed separate evolutionary paths. These divergent strategies of adaptation may make it more difficult for the host species to develop a tolerance to multiple parasites at once."It's important to consider that parasites are constantly evolving, and, in many ways, they have a greater potential to evolve than honeybees because they reproduce quickly," leading researcher Dr. Mikheyev said. "As we're trying to fight these parasites, we have to remember that our target is always moving."

Researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University sequenced the genomes of the two Varroa mite species (V. destructor and V. jacobsoni) that parasitize honey bees, finding that each species used a distinct strategy to survive in its bee host, potentially overwhelming the bees' defenses. In addition to pointing to how scientists might vanquish these deadly intruders, the findings also shed light on how parasites and hosts evolve in response to one another. The species share 99.7% of their DNA, but genetic evidence indicated that the mite species followed separate evolutionary paths. These divergent strategies of adaptation may make it more difficult for the host species to develop a tolerance to multiple parasites at once."It's important to consider that parasites are constantly evolving, and, in many ways, they have a greater potential to evolve than honeybees because they reproduce quickly," leading researcher Dr. Mikheyev said. "As we're trying to fight these parasites, we have to remember that our target is always moving."

More Bees Doing More Math

New research by Dr. Scarlet Howard of Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, suggests that bees continue to climb the rankings of math abilities.

In this experiment, honey bees were trained to enter a Y-shaped maze and given the task of distinguishing between a card with four shapes on it, or another card with either eight, seven, six or five shapes on it. When they correctly selected the card with four shapes, they were rewarded with a sip of sweet sugary water.

But half the bees, when they incorrectly picked the other card, were given a sip of bitter quinine-flavoured water instead. It turns out their success at the task came down to how they'd been trained.

Bees that were trained with the reward when they got the answer right and the penalty when they got the answer wrong performed much better than bees that were trained with the reward alone.

They could distinguish between cards with four and eight shapes on them, and even the trickier choice of distinguishing between four and five.

This puts honey bees on par with humans and mosquitofish.

"It shows us definitively that changing the training regime with the bees ... really impacts their performance on tasks," said lead author of the study, Scarlett Howard, who carried out the research as part of her PhD at RMIT University.