Bee Informed Partnership to Shut Down

In late October, unofficial news came of the imminent shutdown of the Bee Informed Partnership due to funding issues. As many community members know, the Bee Informed Partnership was founded by Dr. Dennis vanEngelsdorp and Karen Rennich and run from the University of Maryland until recently, when it moved to Auburn University.

Projects like the United States Honey Bee Colony Loss Surveys have become a pillar of our understanding of honey bee health and beekeeping practices since 2006, moving to UMD in 2011. Many Maryland beekeepers are also active participant in the pioneering Sentinel Apiaries program.

We understand that the staff of Bee Informed are being let go, but are nonetheless working to move their data and work to other research centers before completing the shutdown. The UMD team is still determining where there are roles that staff can move to within the UMD Honey Bee Research Lab, which continues to operate.

CCBA Beekeeping Course

Swarm Catching Magic

A recent article by Andrew Colletti in Atlas Obscura features former MSBA keynote and beekeeping historian Dr. Gene Kritsky, discussing magic spells used during the Middle Ages to lure honey bees back into their home. Here is one (used primarily by churchmen!)

“Take [some] earth, throw it with your right hand under your right foot, and say:

‘I catch it under foot, I have found it. Lo! Earth has power against all and every being, and against malice and against mindlessness, and against the mighty tongue of man.’

And then throw dust over the bees when they swarm, and say: ‘Sit you, victory-women, settle to earth! Never must you fly wild to the wood. Be you as mindful of my welfare as each man is of his food and home.’”

The article gives a fascinating look back at medieval beekeeping as well as the usual explanation of swarm biology

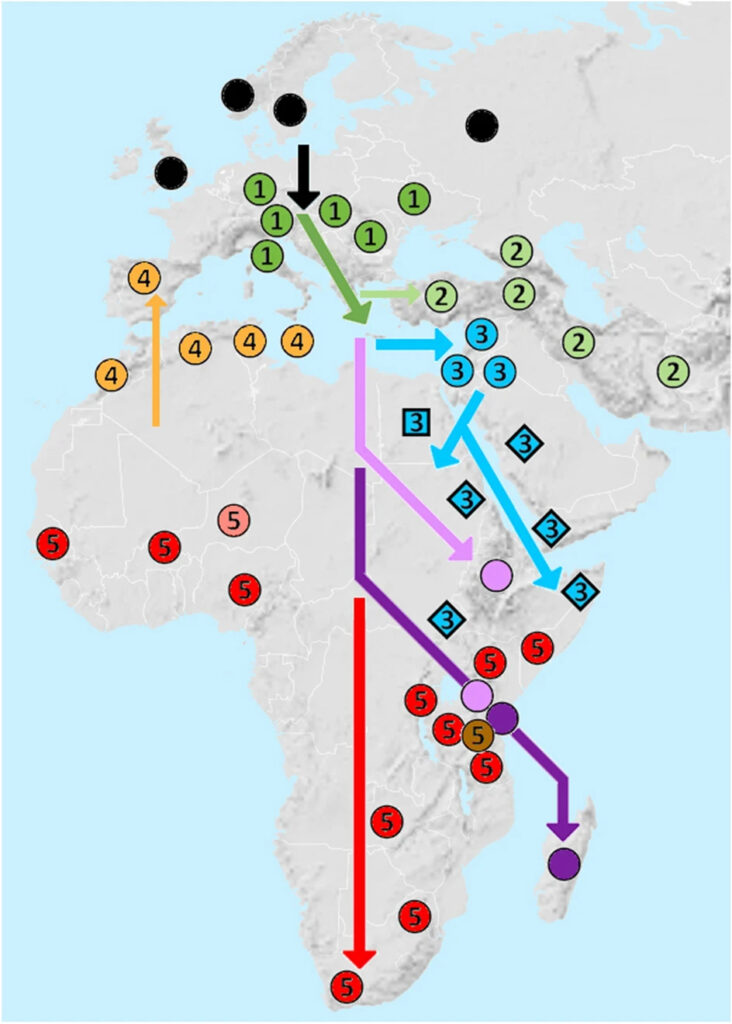

Recent Paper Indicates Apis Mellifera has European Origin

Dr. Steven M. Carr of Memorial University of Newfoundland published a paper in June's Scientific Reports that asserts that existing hypotheses that Western honey bees originated in Africa or Asia is not supported when analyzing mitochondrial DNA. In fact, his work shows instead a basal origin of A. m. mellifera in Europe about 780,000 years ago, followed by expansion to Southeast Europe and Asia Minor. Eurasian bees then spread southward via the Levant into Africa . Professor Carr commented, "The accepted wisdom is that European honey bees evolved from Africa or Asia. It turns the standard picture on its head."

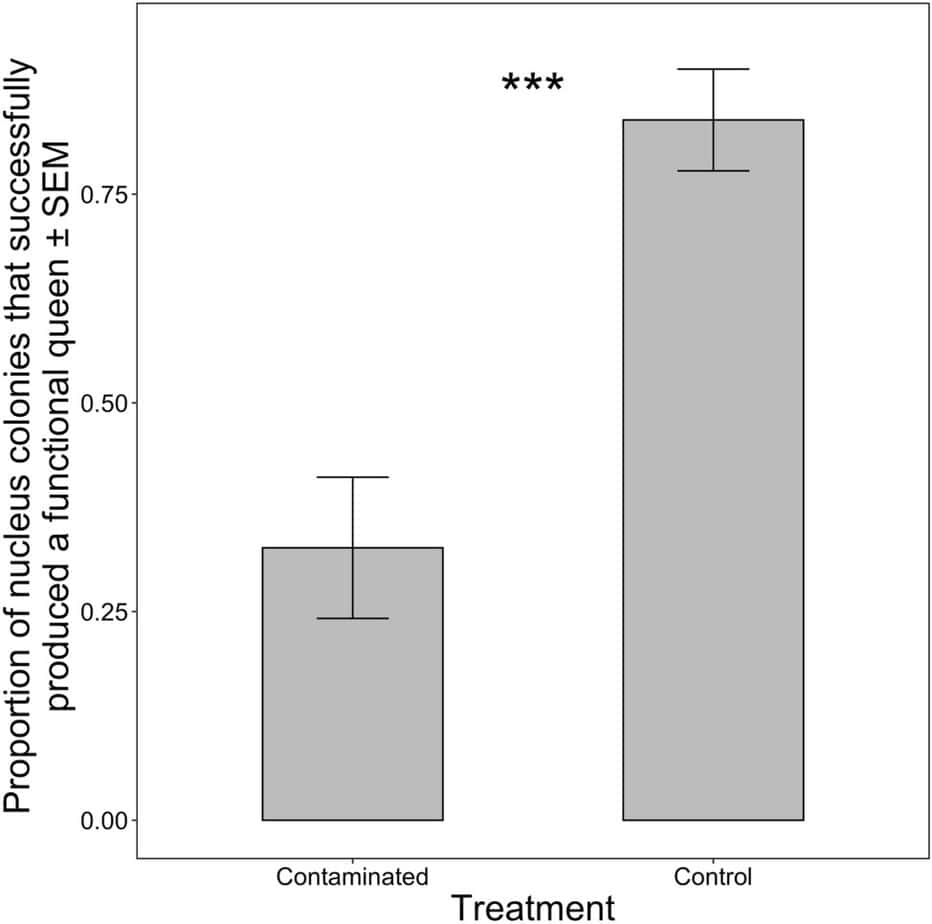

Pesticides a possibility? Rethink re-using that comb

A brand new study published in the October 2023 issue of Scientific Reports shows troubling impacts from re-use of frames from deadouts associated with pesticide contamination. "Re-using food resources from failed honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies and their impact on colony queen rearing capacity" from Drs. Rogan Tokach, Autumn Smart, and Judy Wu-Smart of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln concludes that "colonies given pesticide-contaminated resources (including neonicotinoids) produced fewer queen cells per colony and had a lower proportion of colonies successfully raising a functional, diploid egg-laying queen." Their control group was provided with "clean" frames from deadouts that did not have pesticide exposure, and these colonies produced significantly more queen cells.

Honey Bee Pollination Behavior May Result in Less Fit Plants

In a recent paper from the Royal Society titled "Honeybees (Apis mellifera) decrease the fitness of plants they pollinate," researchers Dillon Travis and Joshua Kohn observed the visitation behavior of Western honey bees versus native pollinators on several California floral speciesin order to gauge the quality of the pollination for plant survival and fitness. Historically, scientists have tried to judge this phenomenon by size -- basically, the number of pollen grains being transferred. In this study, however, the scientists propose that the number of blooms visited on each flower in a single visit may play an important role. Honey bees tend to work many blooms on the same plant before moving on, resulting in what Travis and Kohn theorize may be substantial self-pollination rather than cross-pollination between different members of the same species. Native pollinators are more likely to visit single blooms and then move on. Their conclusion: "Offspring produced after honeybee pollination have similar fitness to those resulting from hand self-pollination and both are far less fit than those produced after pollination by native insects or by cross-pollination."

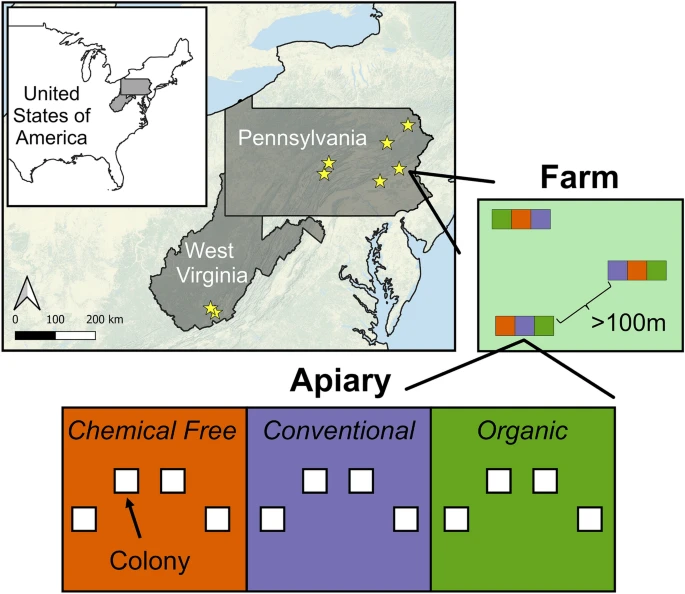

Penn State Study: Organically Managed Colonies are Just as Healthy, Productive

A team led by Robin Underwood of Penn State University published the results of a longitudinal study in Scientific Reports this Spring, finding that honey bee colonies managed using organic methods were as healthy and productive as those managed in conventional systems, while avoiding the use of synthetic pesticides to control pests and pathogens inside the hive. To evaluate the effectiveness of various beekeeping approaches, the researchers studied nearly 300 honey bee colonies located on eight certified organic farms — six in Pennsylvania and two in West Virginia. The research team developed study protocols in collaboration with 30 experienced beekeepers grouped in three broad categories: conventional, chemical free, and organic. Their results show that organic and conventional management systems both increased winter survival by more than 180% compared to chemical-free management. Organic and conventional management also increased total honey production across three years by 118% and 102%, respectively. Organic and conventional management systems did not differ significantly in survival or honey production.

[Return to November 2023 BeeLine newsletter]