Charles DeBarber and the amazing world of antique bee gear restoration

Charles DeBarber of the Filbert Street Garden (and apiary) in Baltimore and the Beeky Geek Youtube channel calls himself "A beekeeper who just loves to restore old hive equipment." His respect and affection for these old tools is evident in the skill and care he uses to bring them back to service.

In his very well produced videos, you can see him remove fragile old leather from a bellows, carefully replicate the piece from a modern day Goodwill find, and place it nail-by-nail into the original metal brackets. Who else seeks out (and finds!) a clockmaker in order to repair an old German clockwork smoker? Who knew that there even were clockwork smokers? DeBarber did.

Charles calls himself "a fanatic for A.I. Root equipment." "I collect bee equipment from all around the world, but I'm a big A.I. Root fanboy."

Depending on the piece, Charles not only returns the tool to functional life: in the case of an old copper Ruddy Smoker, he also cleaned and polished it almost to its original mail-order self. He sprinkles his work with insights into the history of bee gear, design choices made at the time, and how tools changed and why.

Midwinter renovations and recreations

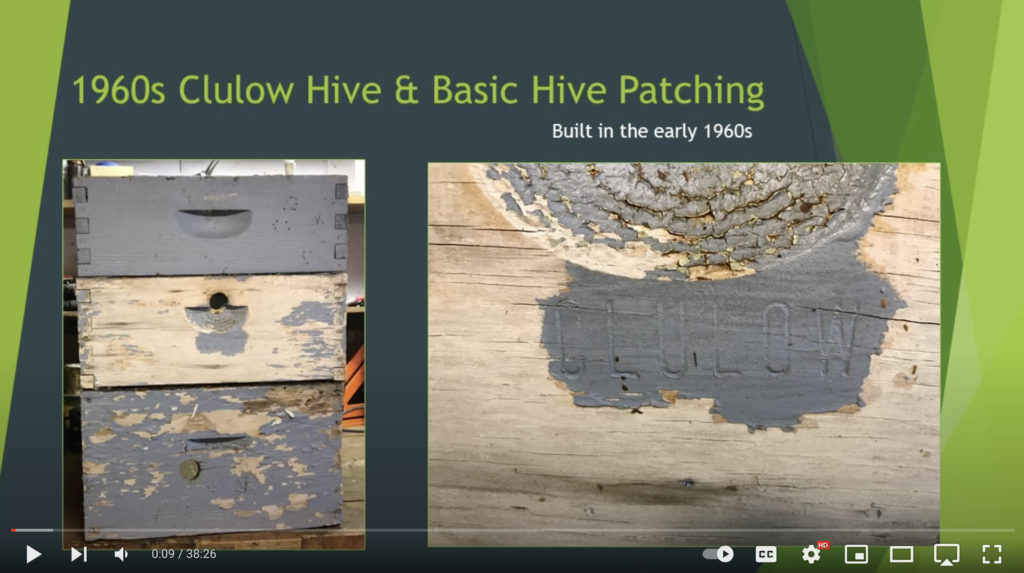

During this part of the year, when we are often introducing our short course students to all the shiny new gear and pristine veils in the beekeeping catalog, Charles is doing something different: He is using the off-season (the only free time he has for painting and nailing and gluing) to patch old hive woodenware. In some cases, he has brought items more than 60 years old back into service, including a hive was built by the late Reverend Clulow, a founder of the Anne Arundel County Beekeeping Association in Central Maryland.

DeBarber suggests that winter is a good time to do this work. The idea is to plan to rotate older boxes out, perhaps every 3-4 years, and to perform maintenance like patching and repainting before Spring demands get rolling.

Though restoration of a box over 50 years old is not a typical task for the rest of us, he tackles topics like warping and rot that do occur even in newer gear. The video linked here includes good, basic information about working with old woodenware, though Charles doesn't consider himself a woodworker. As you would suspect, he is careful to mention the dangers of American Foulbrood from old, unknown equipment, but he flagged one issue that never would have occurred to me: watching out for lead based paint.

Boxes certainly take a beating, and some come out of it in worse shape than others. For that reason, Charles also goes into different patching methods, from ways in which to use wood glue, cases requiring filler, and even replacement of pieces too rotten to continue to serve.

The steps De Barber is willing to take to save wooden box components carrying the historic Clulow brand are probably not those many of us would even consider for normal maintenance. However, his approaches to identifying rot, reversing warping, planing and resurfacing are applicable to most of us in certain cases.

For instance, did you know that patching boxes with new, sound wood is not only possible, but that the most common patch is a thin strip replacing the bottom area of the side of a hive body? Basically, rot is pretty common at the bottom of boxes, where water can collect and hive tools do some damage.

Charles mentions, "Rot is not the primary reason to tilt a hive forward (that's to ensure proper drainage for the bees!), but the minute that the woodenware starts holding water toward the back is a bane for boxes and bottom boards. Beekeeping is already prohibitively expensive. Maintenance and repairs can bring down the overhead dramatically."

You know, it is not for everyone. He mentions that extending the life of a box might depend a lot on the time you have available, your potential nostalgia ("your first hive?"), or maybe the personal or historical significance of a given piece. Or not!

Charles emphasizes methods that create strong solutions that work, maybe not always with fancy results. He demonstrates how to make wood filler, bringing a slightly warped piece into line, strip patching, and wetting/clamping to remedy warping.

When it is time to walk away

Charles' apiary at the Filbert Street Garden started with no resources, and lots of found gear, requiring problem solving and skills like these. The bees at the Garden provide the largest cash crop, supporting a wonderful range of activities there. Even as the garden has grown, and resources have become more plentiful, restoring, reusing, and extending the life of the wooden structures that sheltered bees and helped create a community is important to Charles. He adds, "Yeah, we had next to no money for what is now Maryland's largest community garden beeyard. I was getting used equipment clubs and individuals were tossing out, buying from farm lots that sat in barns for decades, etc. We took what others discarded. Wood glue and scrap lumber are next to nothing."

There does come a time when a box really can't serve like it used to, of course. Well, DeBarber has a suggestion for that, too. Convert it into a swarm trap!